In 2022, Rapide-Blanc Productions released “Greyland” — a documentary inspired by Justin Gest’s 2016 book, 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘕𝘦𝘸 𝘔𝘪𝘯𝘰𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘺: 𝘞𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘞𝘰𝘳𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘊𝘭𝘢𝘴𝘴 𝘗𝘰𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘯 𝘈𝘨𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘐𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘐𝘯𝘦𝘲𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘺. Directed by award-winning French-Canadian filmmaker Alexandra Sicotte-Levesque, the film won the Grand Jury Prize from the Blue Ridge Film Festival, Best Social and Cultural Feature at the Montauk Film Festival, and Best Documentary Prizes at the Red Cedar Film Festival and the Sound + Sight Festival in Ventura, California.

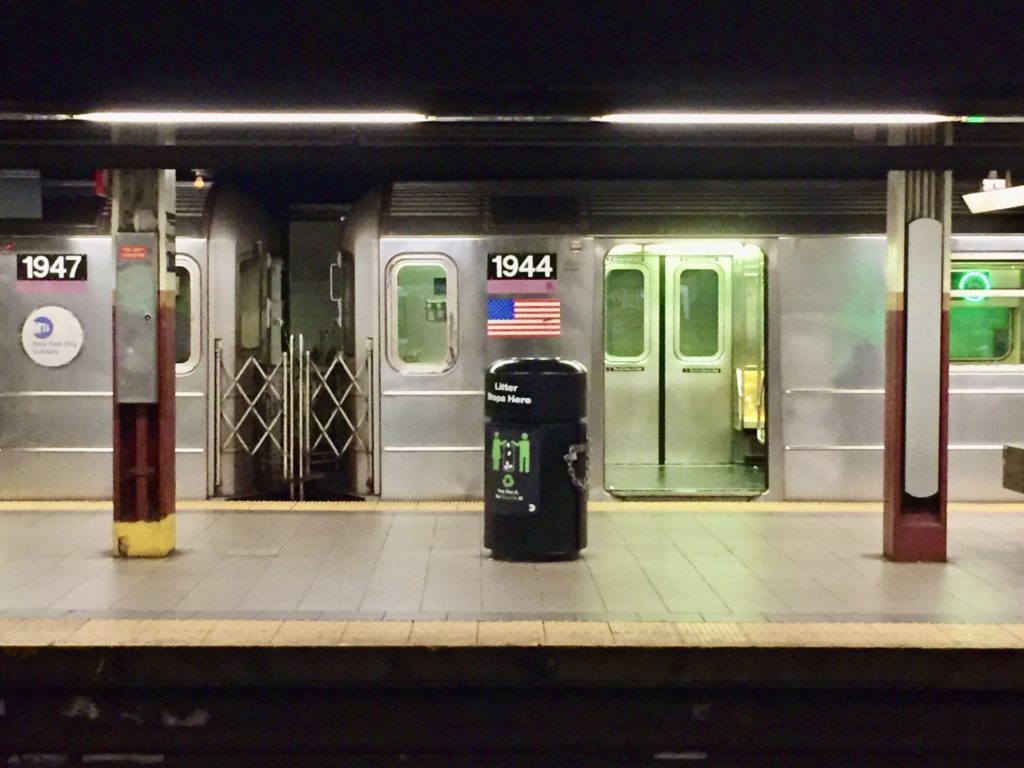

“Greyland” is the story of what was the fastest shrinking city in the United States: Youngstown, Ohio. Once the booming center of American steel, when the bottom fell out of the industry in the 1970s, 60 percent of the population moved out. Among those who remain today, most live beneath the poverty line. Like Rocco and Amber. A recovering heroin addict turned “urban archeologist,” Rocco hunts through hundreds of abandoned houses for vintage clothing, records, and artwork. Everything he finds goes to Greyland — his art gallery-cum-thrift store — to be converted into cash. Amber is a single mother and the president of the Neighborhood Association of Homeowners, leading the fight against City Hall for their inaction in cleaning up her neighborhood.

Through poetically apocalyptic imagery of a town taking its last breath, Greyland tells the story of two individuals’ resilience when everything has fallen apart around them. Greyland follows Rocco and Amber’s search for meaning and hope in the midst of economic decline and a political landscape out of sync with the needs of its community. Should Rocco and Amber continue to fight for their city or flee like thousands before them? ¨Leave if you want to leave,” says Rocco, “but don’t turn it into something it’s not.” What grows back on a city burnt to the ground?